Collaborative Worklow

Introduction

Software is often designed and built as part of a team, so in this episode we'll be looking at how to manage the process of team software development and improve our code by engaging in code review process with other team members.

Collaborative Code Development Models

The way your team provides contributions to the shared codebase depends on the type of development model you use in your project. Two commonly used models are:

fork and pull model - where anyone can fork an existing repository (to create their copy of the project linked to the source) and push changes to their personal fork. A contributor can work independently on their own fork as they do not need permissions on the source repository to push modifications to a fork they own. The changes from contributors can then be pulled into the source repository by the project maintainer on request and after a code review process. This model is popular with open source projects as it reduces the start up costs for new contributors and allows them to work independently without upfront coordination with source project maintainers. So, for example, you may use this model when you are an external collaborator on a project rather than a core team member.

shared repository model - where collaborators are granted push access to a single shared code repository. Even though collaborators have write access to the main development and production branches, the best practice of creating feature branches for new developments and when changes need to be made is still followed. This is to enable easier testing of the new code and initiate code review and general discussion about a set of changes before they are merged into the development branch. This model is more prevalent with teams and organisations collaborating on private projects.

Regardless of the collaborative code development model you and your collaborators use - code reviews are one of the widely accepted best practices for software development in teams and something you should adopt in your development process too.

Code Review

Code review is a software quality assurance practice where one or several people from the team (different from the code's author) check the software by viewing parts of its source code.

Advantages of Code Review

Discuss as a group: what do you think are the reasons behind, and advantages of, code review?

Code review is one of the most useful team code development practices - someone checks your design or code for errors, they get to learn from your solution, having to explain code to someone else clarifies your rationale and design decisions in your mind too, and collaboration helps to improve the overall team software development process. It is universally applicable throughout the software development cycle - from design to development to maintenance. According to Michael Fagan, the author of the code inspection technique, rigorous inspections can remove 60-90% of errors from the code even before the first tests are run (Fagan, 1976). Furthermore, according to Fagan, the cost to remedy a defect in the early (design) stage is 10 to 100 times less compared to fixing the same defect in the development and maintenance stages, respectively. Since the cost of bug fixes grows in orders of magnitude throughout the software lifecycle, it is far more efficient to find and fix defects as close as possible to the point where they were introduced.

There are several code review techniques with various degree of formality and the use of a technical infrastructure, here we will be using a Tool-assisted code review , using GitHub's Pull Requests. It is a lightweight tool, included with GitHub's core service for free and has gained popularity within the software development community in recent years. This tool helps with the following tasks: (1) collecting and displaying the updated files and highlighting what has changed, (2) facilitating a conversation between team members (reviewers and developers), and (3) allowing code administrators and product managers a certain control and overview of the code development workflow.

Adding code via GitHub's Pull Requests

Pull requests are fundamental to how teams review and improve code on GitHub (and similar code sharing platforms) - they let you tell others about changes you've pushed to a branch in a repository on GitHub and that your code is ready for review. Once a pull request is opened, you can discuss and review the potential changes with others on the team and add follow-up commits based on the feedback before your changes are merged from your feature branch into the base branch.

How you create your feature branches and open pull requests in GitHub will depend on your collaborative code development model:

In the shared repository model, in order to create a feature branch and open a pull request based on it you must have write access to the source repository or, for organisation-owned repositories, you must be a member of the organisation that owns the repository. Once you have access to the repository, you proceed to create a feature branch on that repository directly.

In the fork and pull model, where you do not have write permissions to the source repository, you need to fork the repository first before you create a feature branch (in your fork) to base your pull request on.

In both development models, it is recommended to create a feature branch for your work and the subsequent pull request, even though you can submit pull requests from any branch or commit. This is because, with a feature branch, you can push follow-up commits as a response to feedback and update your proposed changes within a self-contained bundle.

The only difference in creating a pull request between the two models is how you create the feature branch. In either model, once you are ready to merge your changes in - you will need to specify the base branch and the head branch.

Issues, Pull Requests and Code Review In Action

Let's see this in action - you and your fellow learners are going to be organised in small teams and assume to be collaborating in the shared repository model. You will be added as a collaborator to another team member's repository (which becomes the shared repository in this context) and, likewise, you will add other team members as collaborators on your repository. You can form teams of two and work on each other's repositories. If there are 3 members in your group you can go in a round robin fashion (the first team member does a pull request on the second member's repository and receives a pull request on their repository from the third team member). If you are going through the material on your own and do not have a collaborator, you can do pull requests on your own repository from one to another branch.

Recall the oxrse_unit_conv repo that you cloned previously (https://github.com/OxfordRSE/oxrse_unit_conv). This is a small

toy Python project that implements some classes for SI and non-SI units (you can

read the README.md file for more information), and implements convertions

between values of different units.

In the previous section you each implemented an issue to add a new feature (e.g. a new unit) or bugfix. Now your taks is to implement this feature or bugfix, along with tests to make sure your new code works correctly or that the bug is fixed. You can use the existing tests as a guide for how to write new tests. You can also use the existing tests to ensure that your changes do not break any existing functionality.

You will propose changes to their repository (the shared repository in this context) via issues and pull requests (acting as the code author) and engage in code review with your team member (acting as a code reviewer). Similarly, you will receive a pull request on your repository from another team member, in which case the roles will be reversed. The following diagram depicts the branches that you should have in the repository.

Adapted from Git Tutorial by sillevl (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License)

To achieve this, the following steps are needed.

Step 1: Adding Collaborators to a Shared Repository

You need to add the other team member(s) as collaborator(s) on your repository to enable them to create branches and pull requests. To do so, each repository owner needs to:

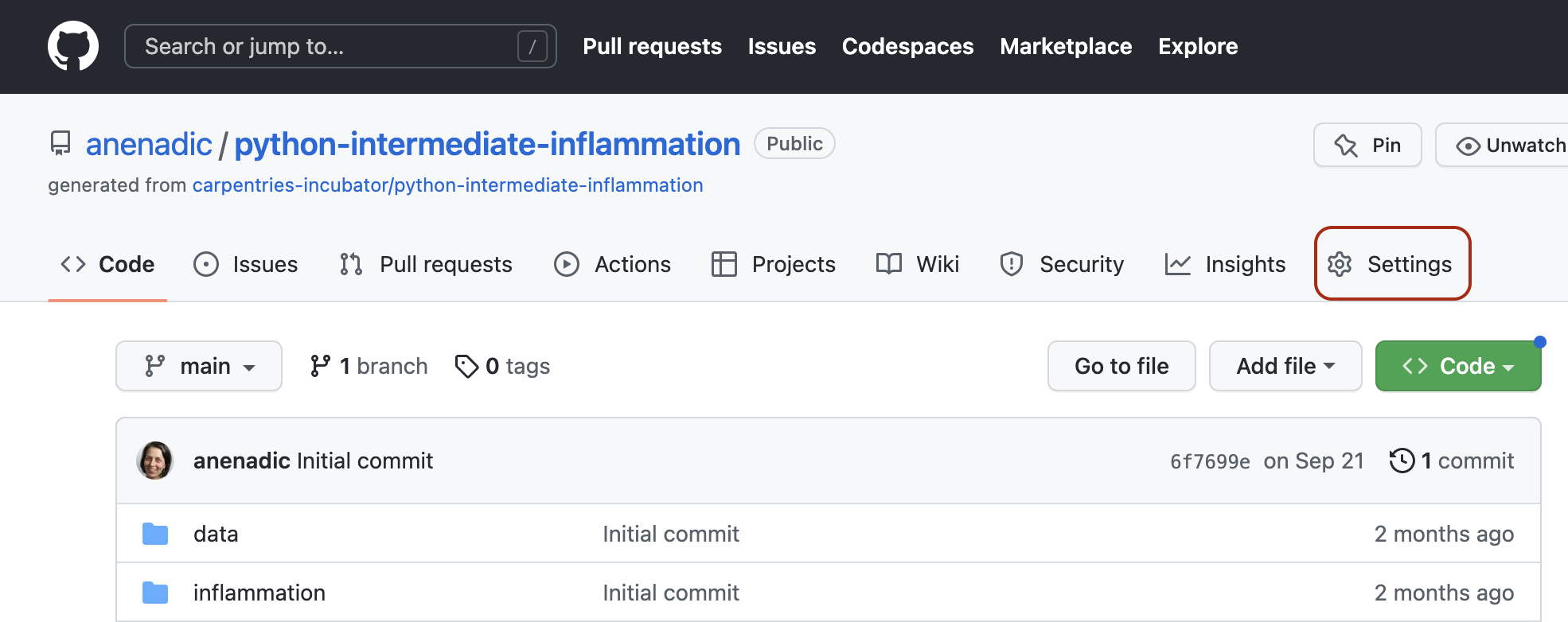

Head over to Settings section of your software project's repository in GitHub.

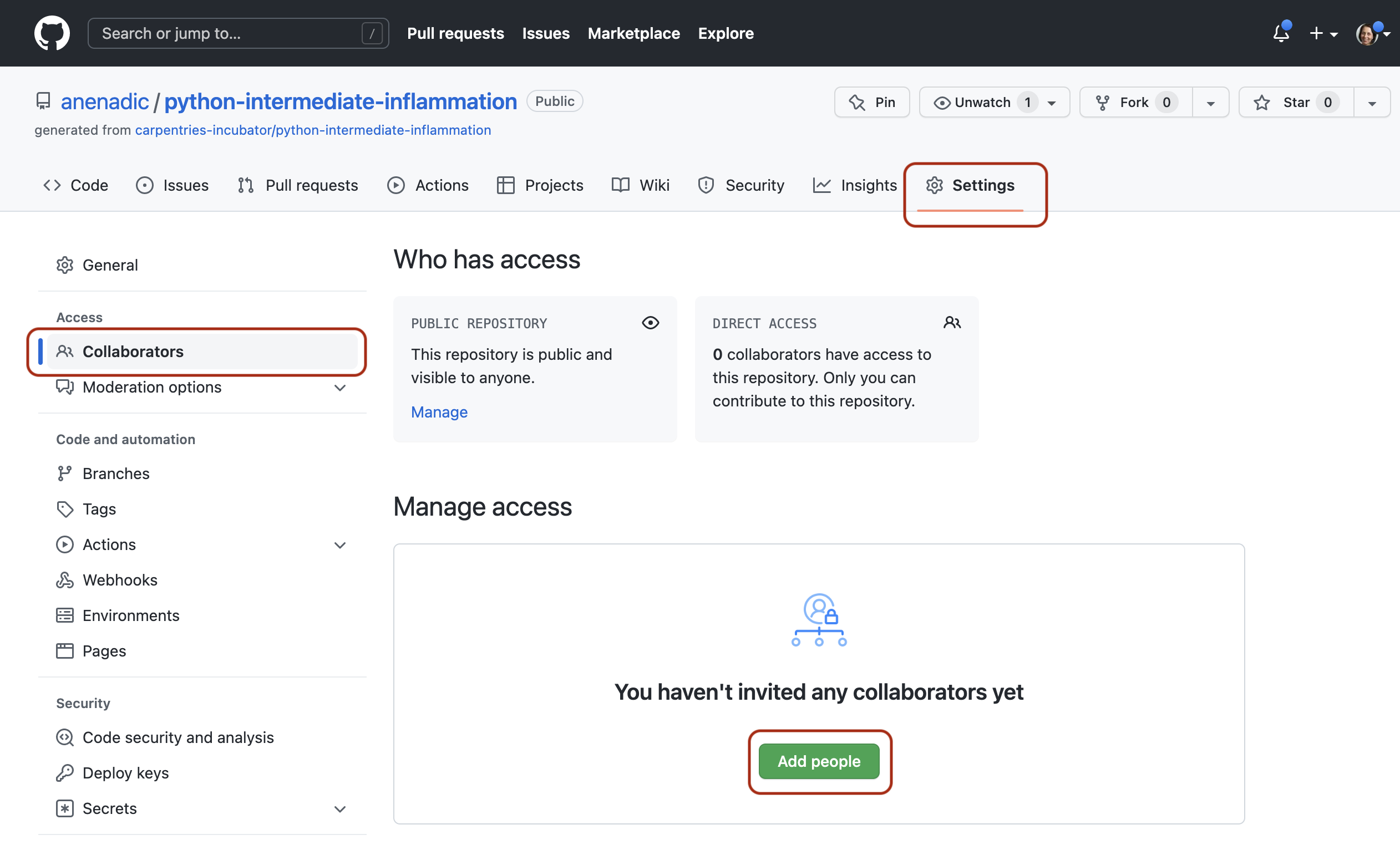

Select the vertical tab 'Collaborators' from the left and click the 'Add people' button.

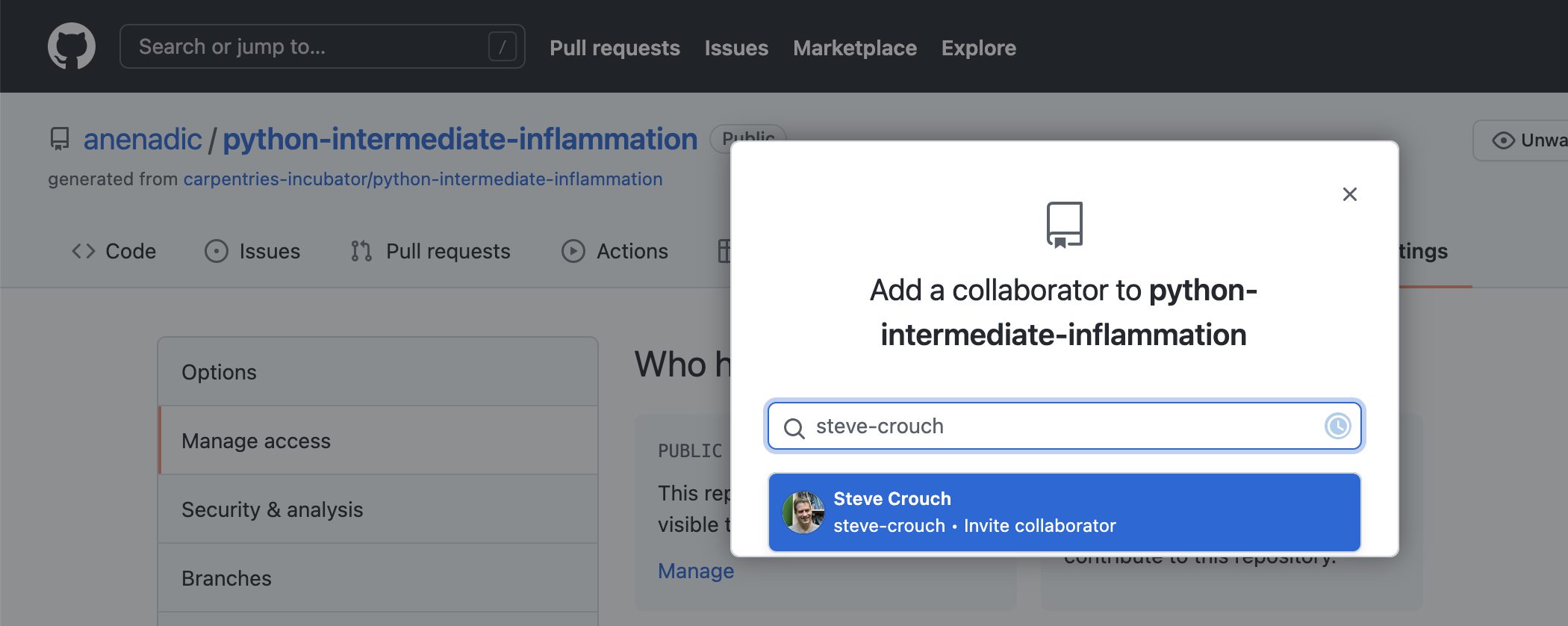

Add your collaborator(s) by their GitHub username(s), full name(s) or email address(es).

Collaborator(s) will be notified of your invitation to join your repository based on their notification preferences.

Once they accept the invitation, they will have the collaborator-level access to your repository and will show up in the list of your collaborators.

See the full details on collaborator permissions for personal repositories to understand what collaborators will be able to do within your repository. Note that repositories owned by an organisation have a more granular access control compared to that of personal repositories.

Step 2: Create an issue for the feature you are going to implement

You might already have an issue from the previous section, but if not, head over to the "Issues" tab and create a new issue that you will implement.

Step 3: Create a Feature Branch

Obtain the GitHub URL of the shared repository you will be working on and clone it locally if you havn't already. This will create a copy of the repository locally on your machine along with all of its (remote) branches.

git clone <remote-repo-url> cd <remote-repo-name>Organise within you team what naming convention you will use for new branches. A common choice it to use the issue number and one or more keywords, for example

i23-feature-name.Create and checkout the new branch in your local repository

git checkout -b i23-feature-nameYou are now located in the new (local)

i23-feature-namebranch and are ready to start adding your code.

Step 4: Adding New Code

Implement Feature/Bugfix and Tests

Now implement the new feature or bugfix that you have described in your issue. It is a good idea to commit often while developing, providing you with a history of commits you can go back to, and others in your team with information of development progressing elsewhere in the collaboration. You can "tag" a commit with an issue by including an issue number reference (e.g. "#23") in the commit message.

git add -A git commit -m "#23 add test for unit nmol/sec"

Make sure you write tests to ensure that the bug has been fixed or the feature works as expected. For a bug fix, you effectivly start with a test which is simply the code that leads to this bug. Then its a matter of implementing fixes until the test passes. For a feature you can either start off by writing a test that illustrates how you will implement the feature, and will pass once this is done (this is normally given the name "Test-Driven Development"), or you can test the feature once you have written it to check that the code works.

Testing Based on Requirements

Tests should test functionality, which stem from the software requirements, rather than an implementation. Tests can be seen as a reflection of those requirements - checking if the requirements are satisfied.

Remember to commit your new code to your branch feature-x-tests.

Step 5: Submitting a Pull Request

When you have finished adding your code and tests and have committed the changes to your

local i23-feature-name, and are ready for the others in the team to review them, you

have to do the following:

Push your local feature branch

i23-feature-nameremotely to the shared repository.git push -u origin i23-feature-nameNormally step one will provide a handy url for you to create the PR. However, if not, or you wish to do it manualy, Head over to the remote repository in GitHub and locate your new (

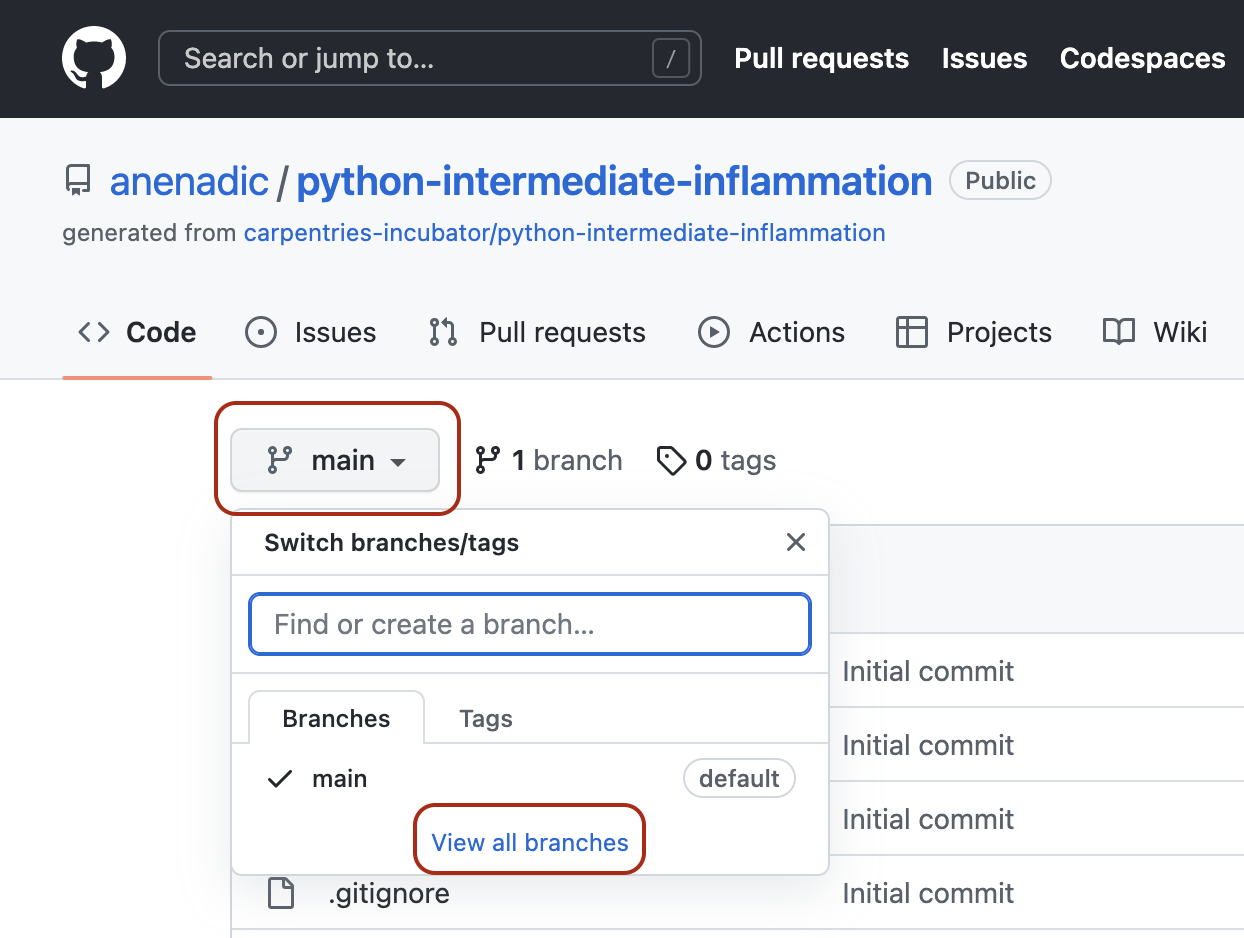

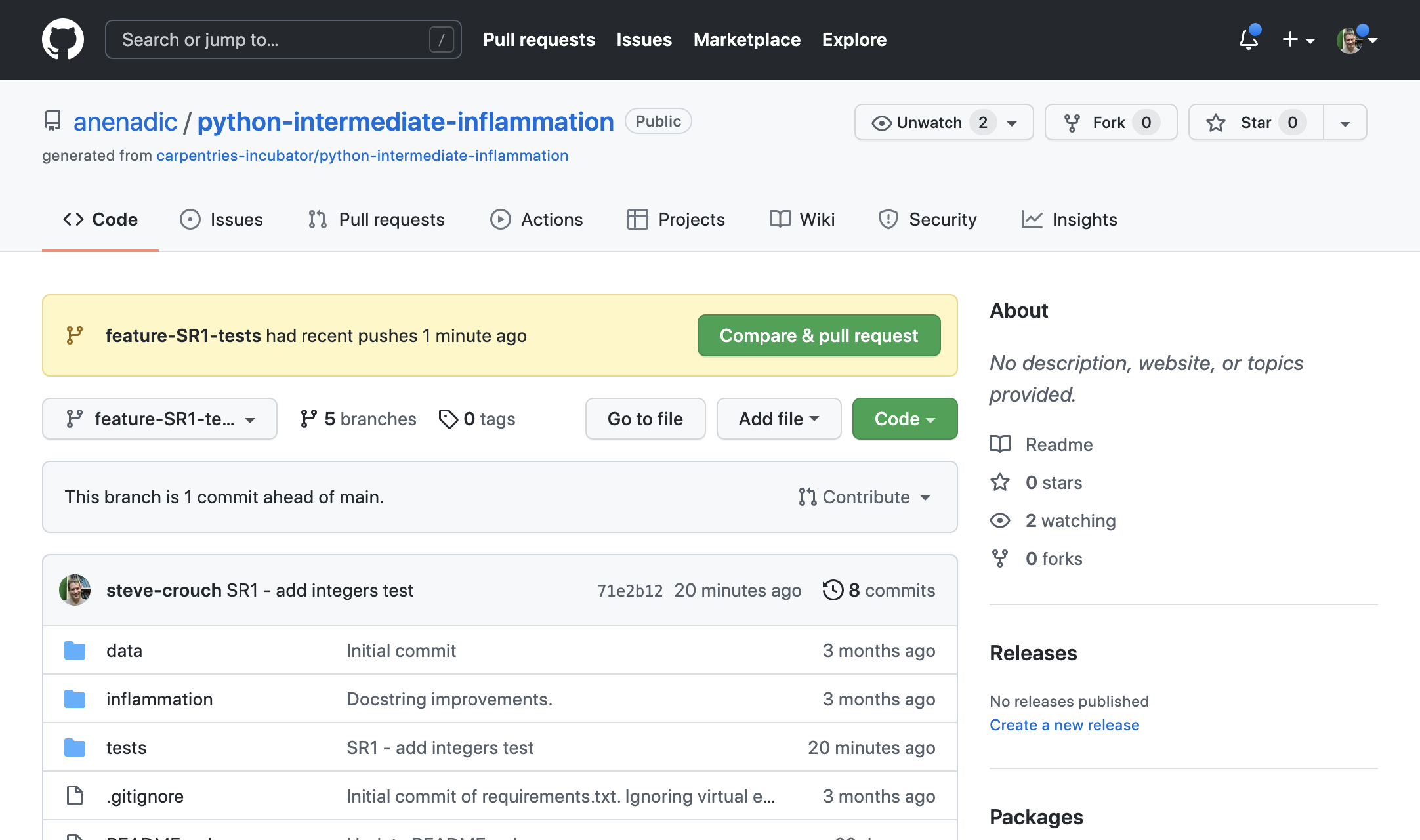

i23-feature-name) branch from the dropdown box on the Code tab (you can search for your branch or use the "View all branches" option).

Open a pull request by clicking "Compare & pull request" button.

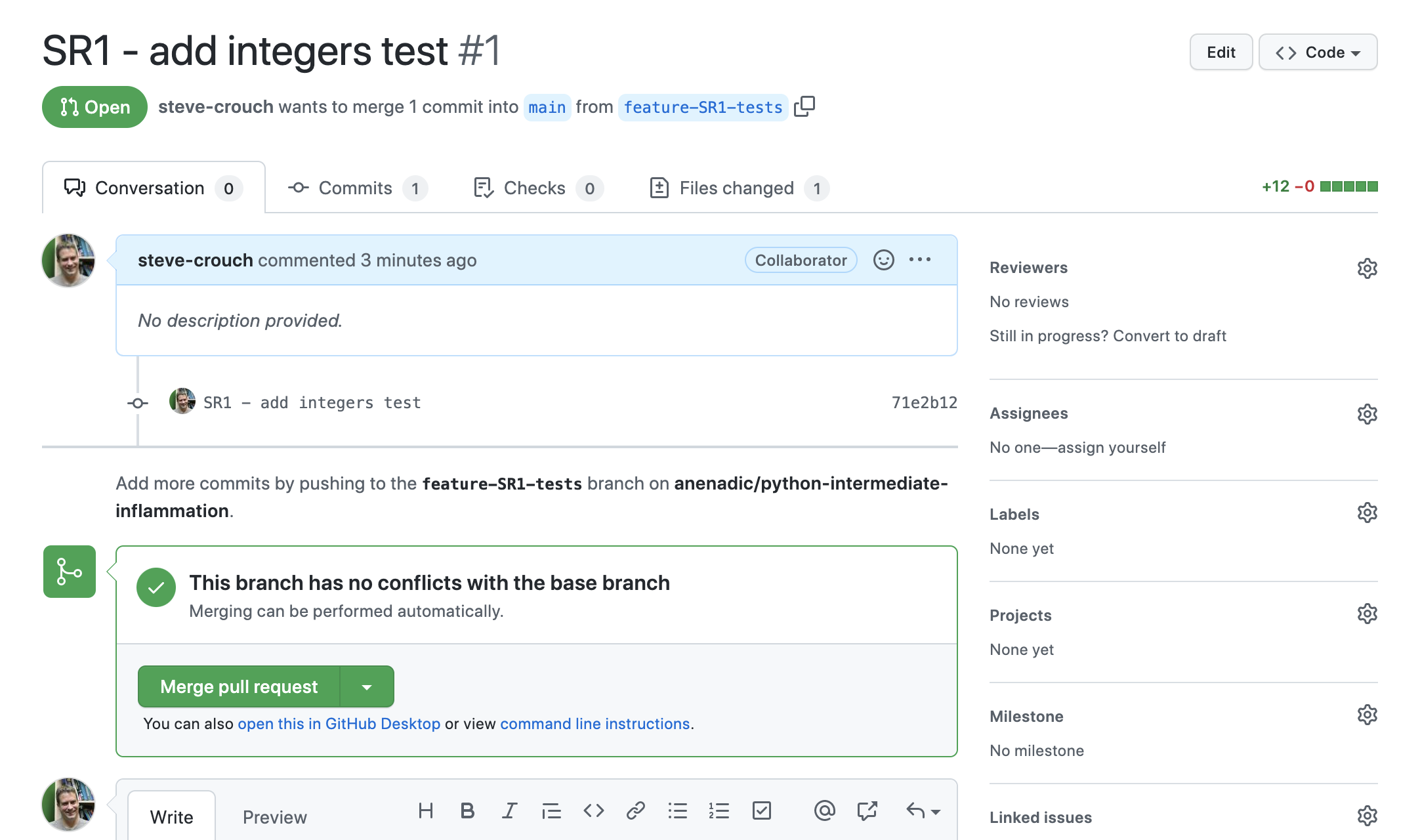

Select the base and the head branch, e.g.

mainandi23-feature-name, respectively. Recall that the base branch is where you want your changes to be merged and the head branch contains your changes.Add a comment describing the nature of the changes, and then submit the pull request.

Repository moderator and other collaborators on the repository (code reviewers) will be notified of your pull request by GitHub.

At this point, the code review process is initiated.

You should receive a similar pull request from other team members on your repository.

Step 6: Code Review

The repository moderator/code reviewers reviews your changes and provides feedback to you in the form of comments.

Respond to their comments and do any subsequent commits, as requested by reviewers.

The tests are automatically run by the Continuous Integration setup via Github Actions, and a report will be generated. Once all tests pass your PR will be given a nice green tick.

It may take a few rounds of exchanging comments, discussions, and additional commits until the team is ready to accept your changes and all tests pass.

Perform the above actions on the pull request you received, this time acting as the moderator/code reviewer.

Step 7: Closing a Pull Request

Once the moderator approves your changes and all tests pass, either one of you can merge onto the base branch (who actually does the merging may differ from team to team).

Delete the merged branch to reduce the clutter in the repository.

Repeat the above actions for the pull request you received.

If the work on the feature branch is completed and it is sufficiently tested, the

feature branch can now be merged into the main branch.

Best Practice for Code Review

There are multiple perspectives to a code review process - from general practices to technical details relating to different roles involved in the process. It is critical for the code's quality, stability and maintainability that the team decides on this process and sticks to it. Here are some examples of best practices for you to consider (also check these useful code review blogs from Swarmia and Smartbear):

Decide the focus of your code review process, e.g., consider some of the following:

code design and functionality - does the code fit in the overall design and does it do what was intended?

code understandability and complexity - is the code readable and would another developer be able to understand it?

tests - does the code have automated tests?

naming - are names used for variables and functions descriptive, do they follow naming conventions?

comments and documentation - are there clear and useful comments that explain complex designs well and focus on the "why/because" rather than the "what/how"?

Do not review code too quickly and do not review for too long in one sitting. According to “Best Kept Secrets of Peer Code Review” (Cohen, 2006) - the first hour of review matters the most as detection of defects significantly drops after this period. Studies into code review also show that you should not review more than 400 lines of code at a time. Conducting more frequent shorter reviews seems to be more effective.

Decide on the level of depth for code reviews to maintain the balance between the creation time and time spent reviewing code - e.g. reserve them for critical portions of code and avoid nit-picking on small details. Try using automated checks and linters when possible, e.g. for consistent usage of certain terminology across the code and code styles.

Communicate clearly and effectively - when reviewing code, be explicit about the action you request from the author.

Foster a positive feedback culture:

give feedback about the code, not about the author

accept that there are multiple correct solutions to a problem

sandwich criticism with positive comments and praise

Utilise multiple code review techniques - use email, pair programming, over-the-shoulder, team discussions and tool-assisted or any combination that works for your team. However, for the most effective and efficient code reviews, tool-assisted process is recommended.

From a more technical perspective:

use a feature branch for pull requests as you can push follow-up commits if you need to update your proposed changes

avoid large pull requests as they are more difficult to review. You can refer to some studies and Google recommendations as to what a "large pull request" is but be aware that it is not exact science.

don't force push to a pull request as it changes the repository history and can corrupt your pull request for other collaborators

use pull request states in GitHub effectively (based on your team's code review process) - e.g. in GitHub you can open a pull request in a

DRAFTstate to show progress or request early feedback;READY FOR REVIEWwhen you are ready for feedback;CHANGES REQUESTEDto let the author know they need to fix the requested changes or discuss more;APPROVEDto let the author they can merge their pull request.

Code Review in Your Own Working Environment

At the start of this episode we briefly looked at a number of techniques for doing code review, and as an example, went on to see how we can use GitHub Pull Requests to review team member code changes. Finally, we also looked at some best practices for doing code reviews in general.

Now think about how you typically develop code, and how you might institute code review practices within your own working environment. Write down briefly for your own reference (perhaps using bullet points) some answers to the following questions:

Which 2 or 3 key circumstances would code review be most useful for you and your colleagues?

Referring to the first section of this episode above, which type of code review would be most useful for each circumstance (and would work best within your own working environment)?

Taking one of these circumstances where code review would be most beneficial, how would you organise such a code review, e.g.:

Which aspects of the codebase would be the most useful to cover?

How often would you do them?

How long would the activity take?

Who would ideally be involved?

Any particular practices you would use?

Key Points

Code review is a team software quality assurance practice where team members look at parts of the codebase in order to improve their code's readability, understandability, quality and maintainability.

It is important to agree on a set of best practices and establish a code review process in a team to help to sustain a good, stable and maintainable code for many years.