Phase Planes and Stability

YouTube lecture recording from October 2020

The following YouTube video was recorded for the 2020 iteration of the course.

The material is still very similar:

Recap from previous parts

2-D linear systems can be solved analytically

Eigenvalues are important

Some larger systems can be simplified

Phase planes, nullclines and fixed points allow us to understand the behaviour

Example from previous lecture

x ˙ = x ( 1 − x ) − x y , y ˙ = y ( 2 − y ) − 3 x y . \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= x(1-x) -xy,\\

\dot{y} &= y\left(2-y\right) - 3xy.

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = x ( 1 − x ) − x y , = y ( 2 − y ) − 3 x y . Linear ODEs for understanding nonlinear

x ˙ = d x d t = λ 1 x , y ˙ = d y d t = λ 2 y , \begin{align*}

\dot{x} = \frac{\rm{d}x}{\rm{d}t} &= \lambda_1 x,\\

\dot{y} = \frac{\rm{d}y}{\rm{d}t} &= \lambda_2 y,

\end{align*} x ˙ = d t d x y ˙ = d t d y = λ 1 x , = λ 2 y , has a fixed point or steady state where x ˙ = y ˙ = 0 \;\dot{x}=\dot{y}=0\; x ˙ = y ˙ = 0

Solutions look like x = A e λ 1 t \;x=Ae^{\lambda_1 t}\; x = A e λ 1 t y = B e λ 2 t \;y=Be^{\lambda_2 t}\; y = B e λ 2 t λ 1 \;\lambda_1\; λ 1 λ 2 . \;\lambda_2. λ 2 .

If λ 1 < 0 \;\lambda_1 < 0\; λ 1 < 0 λ 2 < 0 \;\lambda_2 < 0\; λ 2 < 0 λ 1 \;\lambda_1\; λ 1 λ 2 \;\lambda_2\; λ 2

Adding in a constant (inhomogeneous) component shifts the fixed point

away from the origin. Where is the fixed point of

x ˙ = λ 1 x + 10 , y ˙ = λ 2 y + 10 ? \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= \lambda_1 x + 10,\\

\dot{y} &= \lambda_2 y + 10?

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = λ 1 x + 10 , = λ 2 y + 10 ? Coupling the system has the effect of altering the principle directions over

which the exponential terms apply (changing the basis ).

This means that the homogeneous linear system

x ˙ = a x + b y , y ˙ = c x + d y , \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= a x + b y,\\

\dot{y} &= c x + d y,

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = a x + b y , = c x + d y , has a fixed point at the origin. The long-term growth or shrinkage of solutions over time is determined by the eigenvalues of the matrix

A = ( a b c d ) \displaystyle A = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{pmatrix} A = ( a c b d )

More generally, the inhomogeneous linear system

x ˙ = a x + b y + p , y ˙ = c x + d y + q , \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= a x + b y + p,\\

\dot{y} &= c x + d y + q,

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = a x + b y + p , = c x + d y + q , ( x ˙ y ˙ ) = ( a b c d ) ( x y ) + ( p q ) . \left(

\begin{array}{c} \dot{x} \\ \dot{y} \end{array}

\right) =

\left(

\begin{array}{cc} a & b \\ c& d \end{array}

\right)

\left(

\begin{array}{c} x \\ y \end{array}

\right)

+

\left(

\begin{array}{c} p \\ q \end{array}

\right)

. ( x ˙ y ˙ ) = ( a c b d ) ( x y ) + ( p q ) . ( x y ) = − ( a b c d ) − 1 ( p q ) . \left(

\begin{array}{c} x \\ y \end{array}

\right) =

-\left(

\begin{array}{cc} a & b \\ c& d \end{array}

\right)^{-1}

\left(

\begin{array}{c} p \\ q \end{array}

\right)

. ( x y ) = − ( a c b d ) − 1 ( p q ) . The long-term growth or shrinkage of

solutions over time is again determined by the eigenvalues of the matrix.

General nonlinear system steady states

A more general two-dimensional nonlinear system is

x ˙ = f ( x , y ) , y ˙ = g ( x , y ) , \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= f(x,y),\\

\dot{y} &= g(x,y),

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = f ( x , y ) , = g ( x , y ) , where f \;f\; f g \;g\; g

We can write a polynomial (Taylor) expansion for the system when it is close to a fixed point:

( x ∗ , y ∗ ) \displaystyle \;(x^*, y^*)\; ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) f ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) = g ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) = 0. \;f(x^*,y^*)=g(x^*,y^*)=0. f ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) = g ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) = 0.

x ˙ = f ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) + ∂ f ∂ x ( x − x ∗ ) + ∂ f ∂ y ( y − y ∗ ) + … , y ˙ = g ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) + ∂ g ∂ x ( x − x ∗ ) + ∂ g ∂ y ( y − y ∗ ) + … , \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= f(x^*,y^*) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x-x^*) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(y-y^*) + \ldots,\\

\dot{y} &= g(x^*,y^*) + \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}(x-x^*) + \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}(y-y^*) + \ldots,

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = f ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) + ∂ x ∂ f ( x − x ∗ ) + ∂ y ∂ f ( y − y ∗ ) + … , = g ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) + ∂ x ∂ g ( x − x ∗ ) + ∂ y ∂ g ( y − y ∗ ) + … , So, close to the fixed point:

( x ˙ y ˙ ) ≈ ( ∂ f ∂ x ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ) ( x − x ∗ y − y ∗ ) . \left(

\begin{array}{c} \dot{x} \\ \dot{y} \end{array}

\right)

\approx

\left(

\begin{array}{cc} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\\frac{\partial g}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial y} \end{array}

\right)

\left(

\begin{array}{c} x-x^* \\ y-y^* \end{array}

\right)

. ( x ˙ y ˙ ) ≈ ( ∂ x ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ) ( x − x ∗ y − y ∗ ) . This means that (really close to the fixed point) we can approximate

with a linear system. The eigenvalues λ 1 , λ 2 \;\lambda_1,\;\lambda_2\; λ 1 , λ 2

J = ( ∂ f ∂ x ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ) J = \left(

\begin{array}{cc} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\\frac{\partial g}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial y} \end{array}

\right) J = ( ∂ x ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ) will determine if a small perturbation away from ( x ∗ , y ∗ ) \;(x^*,\;y^*)\; ( x ∗ , y ∗ )

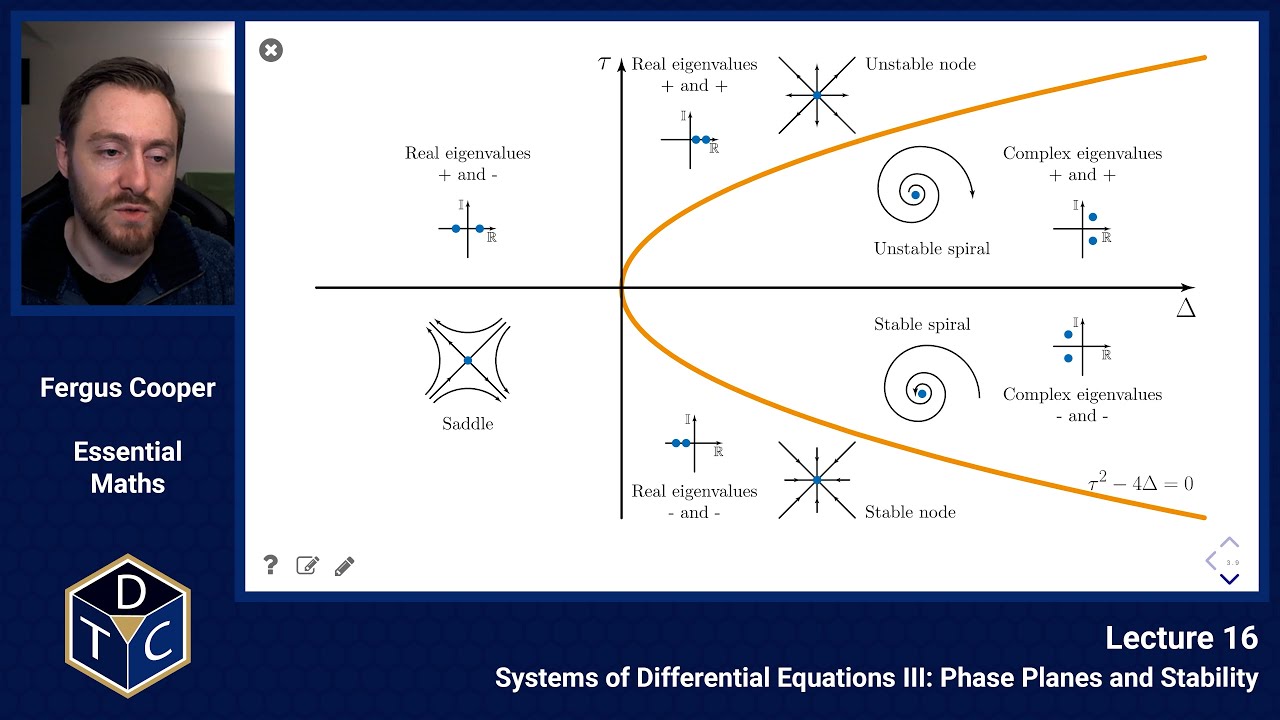

Steady state classification

J = ( ∂ f ∂ x ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ) J = \left(

\begin{array}{cc} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\\frac{\partial g}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial y} \end{array}

\right) J = ( ∂ x ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g )

λ 1 < λ 2 < 0 \lambda_1<\lambda_2<0 λ 1 < λ 2 < 0

λ 1 = λ 2 < 0 \lambda_1=\lambda_2<0 λ 1 = λ 2 < 0

λ 1 > λ 2 > 0 \lambda_1>\lambda_2>0 λ 1 > λ 2 > 0

λ 1 = λ 2 > 0 \lambda_1=\lambda_2>0 λ 1 = λ 2 > 0

λ 1 < 0 < λ 2 \lambda_1<0<\lambda_2 λ 1 < 0 < λ 2

Complex λ \lambda λ

Imaginary λ \lambda λ

The presence of negative eigenvalues determines whether a steady state is physically viable.

Eigenvalues of J J J

∣ J − λ I ∣ = ∣ ∂ f ∂ x − λ ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y − λ ∣ = ( ∂ f ∂ x − λ ) ( ∂ g ∂ y − λ ) − ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x |J-\lambda I| = \left|

\begin{array}{cc} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}-\lambda & \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\\frac{\partial g}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}-\lambda \end{array}\right|

= \left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}-\lambda\right)\left(\frac{\partial g}{\partial y}-\lambda\right)-\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\frac{\partial g}{\partial x} ∣ J − λ I ∣ = ∂ x ∂ f − λ ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g − λ = ( ∂ x ∂ f − λ ) ( ∂ y ∂ g − λ ) − ∂ y ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g So eigenvalues λ \;\lambda\; λ

λ 2 − λ ( ∂ f ∂ x + ∂ g ∂ y ) + ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y − ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x , \lambda^2 - \lambda\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}\right) + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\frac{\partial g}{\partial y} - \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}\frac{\partial g}{\partial x}, λ 2 − λ ( ∂ x ∂ f + ∂ y ∂ g ) + ∂ x ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g − ∂ y ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g , λ 2 − λ τ + Δ w h e r e τ = T r a c e ( J ) a n d Δ = D e t ( J ) \lambda^2 - \lambda\tau + \Delta \quad \rm{where} \quad \tau=\rm{Trace}(J) \quad and \quad \Delta = \rm{Det}(J) λ 2 − λ τ + Δ where τ = Trace ( J ) and Δ = Det ( J ) Example system

x ˙ = x ( 1 − x ) − x y = f ( x ) y ˙ = y ( 2 − y ) − 3 x y = g ( x ) . \begin{align*}

\dot{x} &= x(1-x) -xy &=f(x)\\

\dot{y} &= y\left(2-y\right) - 3xy &=g(x).

\end{align*} x ˙ y ˙ = x ( 1 − x ) − x y = y ( 2 − y ) − 3 x y = f ( x ) = g ( x ) .

What are the fixed points?

What is the stability of the fixed points?

Calculate the Jacobian

J = ( ∂ f ∂ x ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ) = ( − 2 x − y + 1 − x − 3 y − 3 x − 2 y + 2 ) J = \left(

\begin{array}{cc} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \\\frac{\partial g}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial y} \end{array}

\right) = \left(\begin{array}{cc} -2x-y+1 & -x \\-3y & -3x-2y+2 \end{array}\right) J = ( ∂ x ∂ f ∂ x ∂ g ∂ y ∂ f ∂ y ∂ g ) = ( − 2 x − y + 1 − 3 y − x − 3 x − 2 y + 2 ) J ( 0 , 0 ) = ( 1 0 0 2 ) J_{(0,0)} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\0 & 2 \end{array}\right) J ( 0 , 0 ) = ( 1 0 0 2 ) ∣ 1 − λ 0 0 2 − λ ∣ ⟹ λ 1 = 1 , λ 2 = 2 ( u n s t a b l e ) \left|\begin{array}{cc} 1-\lambda & 0 \\0 & 2-\lambda\end{array}\right|\quad\implies\quad\lambda_1 = 1, \; \lambda_2 = 2 \qquad\rm{(unstable)} 1 − λ 0 0 2 − λ ⟹ λ 1 = 1 , λ 2 = 2 ( unstable ) At ( 1 / 2 , 1 / 2 ) (1/2,1/2) ( 1/2 , 1/2 )

J ( 1 / 2 , 1 / 2 ) = ( − 1 2 − 1 2 − 3 2 − 1 2 ) J_{(1/2,1/2)} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} -\frac{1}{2} & -\frac{1}{2} \\-\frac{3}{2} & -\frac{1}{2} \end{array}\right) J ( 1/2 , 1/2 ) = ( − 2 1 − 2 3 − 2 1 − 2 1 ) ∣ − 1 2 − λ − 1 2 − 3 2 − 1 2 − λ ∣ ⟹ λ ± = 1 2 ± 3 2 ( s a d d l e ) \left|\begin{array}{cc} -\frac{1}{2}-\lambda & -\frac{1}{2} \\-\frac{3}{2} & -\frac{1}{2}-\lambda\end{array}\right|\quad\implies\quad\lambda_\pm = \frac{1}{2} \pm \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \qquad\rm{(saddle)} − 2 1 − λ − 2 3 − 2 1 − 2 1 − λ ⟹ λ ± = 2 1 ± 2 3 ( saddle ) J ( 1 , 0 ) = ( − 1 − 1 0 − 1 ) J_{(1,0)} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} -1 & -1 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array}\right) J ( 1 , 0 ) = ( − 1 0 − 1 − 1 ) ∣ − 1 − λ − 1 0 − 1 − λ ∣ ⟹ λ 1 = λ 2 = − 1 ( s t a b l e ) \left|\begin{array}{cc} -1-\lambda & -1 \\0 & -1-\lambda\end{array}\right|\quad\implies\quad\lambda_1 = \lambda_2 = -1 \qquad\rm{(stable)} − 1 − λ 0 − 1 − 1 − λ ⟹ λ 1 = λ 2 = − 1 ( stable ) J ( 0 , 2 ) = ( − 1 0 − 6 − 2 ) J_{(0,2)} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} -1 & 0 \\ -6 & -2 \end{array}\right) J ( 0 , 2 ) = ( − 1 − 6 0 − 2 ) ∣ − 1 − λ 0 − 6 − 2 − λ ∣ ⟹ λ 1 = − 1 , λ 2 = − 2 ( s t a b l e ) \left|\begin{array}{cc} -1-\lambda & 0 \\-6 & -2-\lambda\end{array}\right|\quad\implies\quad\lambda_1 = -1, \; \lambda_2 = -2 \qquad\rm{(stable)} − 1 − λ − 6 0 − 2 − λ ⟹ λ 1 = − 1 , λ 2 = − 2 ( stable ) If we now look again at the phase plane, after having calculated the stability of the fixed points, we can see that the arrows move towards the stable fixed points, and away from the unstable ones.

Summary

Eigenvalues tell us about the behaviour of linear systems

Eigenvalues tell us about the stability of nonlinear systems

Main problems

These questions are extensions of questions on the previous page.

Main problems 1 Classify the fixed points and discuss stability of the following linear systems:

x ˙ = x + 3 y , y ˙ = − 6 x + 5 y ; \displaystyle \dot{x} = x+3y, \qquad \dot{y}=-6x+5y; x ˙ = x + 3 y , y ˙ = − 6 x + 5 y ;

x ˙ = x + 3 y + 4 , y ˙ = − 6 x + 5 y − 1 ; \displaystyle \dot{x} = x+3y+4, \qquad \dot{y}=-6x+5y-1; x ˙ = x + 3 y + 4 , y ˙ = − 6 x + 5 y − 1 ;

x ˙ = x + 3 y + 1 , y ˙ = − 6 x + 5 y . \displaystyle \dot{x} = x+3y+1, \qquad \dot{y}=-6x+5y. x ˙ = x + 3 y + 1 , y ˙ = − 6 x + 5 y .

Main problems 2 Classify the fixed points and discuss stability of the following nonlinear systems:

x ˙ = − 4 y + 2 x y − 8 y ˙ = 4 y 2 − x 2 ; \displaystyle \dot{x} = -4y+2xy-8 \qquad \dot{y}=4y^2-x^2; x ˙ = − 4 y + 2 x y − 8 y ˙ = 4 y 2 − x 2 ;

x ˙ = y − x 2 + 2 , y ˙ = 2 ( x 2 − y 2 ) . \displaystyle \dot{x} = y-x^2+2, \qquad \dot{y}=2(x^2-y^2). x ˙ = y − x 2 + 2 , y ˙ = 2 ( x 2 − y 2 ) .

Main problems 3 The population of a host, H ( t ) H(t) H ( t ) P ( t ) P(t) P ( t )

d H d T = ( a − b P ) H , d P d T = ( c − d P H ) P , H > 0 , \displaystyle \def\dd#1#2{{\frac{{\rm d}#1}{{\rm d}#2}}} \dd{H}{T}=(a-bP)H,\qquad \dd{P}{T}=(c-\frac{dP}{H})P, \qquad H>0, d T d H = ( a − b P ) H , d T d P = ( c − H d P ) P , H > 0 ,

where a , b , c , d a,b,c,d a , b , c , d

y ˙ = ( 1 − x ) y , x ˙ = α x ( 1 − x y ) , \displaystyle \def\dd#1#2{{\frac{{\rm d}#1}{{\rm d}#2}}} \dot{y} = (1-x)y, \qquad \dot{x}=\alpha x(1-\frac{x}{y}), y ˙ = ( 1 − x ) y , x ˙ = αx ( 1 − y x ) ,

where α = c a \displaystyle \alpha=\frac{c}{a} α = a c

Find and classify the fixed points of these simplified equations.

Sketch the phase flow diagram including these fixed points and the information from the previous sketch.

That is, include the flow across:

y = β x \displaystyle y=\beta x y = β x β \beta β

Main problems 4 In the previous parts of this question a model of fish and anglers was developed and simplified.

This question analyses the simplified model.

The simplified version of the model is

x ˙ = r x ( 1 − x ) − x y , y ˙ = β x − y \displaystyle \dot{x} = rx(1 - x) - xy,\qquad \dot{y} = \beta x - y x ˙ = r x ( 1 − x ) − x y , y ˙ = β x − y

where x x x y y y x ˙ \dot{x} x ˙

Calculate the steady states of the system.

Determine the stability of the fixed points in the case β = r = 4 \beta = r = 4 β = r = 4

Draw the phase plane, including the nullclines and phase trajectories.

Extension problems

Extension problems 1 A population F F F H H H

d H d T = a H − b H F ( H > 0 ) , d F d T = c H F − d F ( F > 0 ) . \def\dd#1#2{{\frac{{\rm d}#1}{{\rm d}#2}}}

\begin{aligned}

\dd{H}{T} &= aH-bHF\quad &(H>0),\\

\dd{F}{T} &= cHF-dF\quad &(F>0).

\end{aligned} d T d H d T d F = a H − b H F = cH F − d F ( H > 0 ) , ( F > 0 ) .

Define the four variables a , b , c , d a,b,c,d a , b , c , d

Find the fixed point of the system and describe the motion in its neighbourhood.

What does this mean in terms of the population of hares and foxes?